Entrevista: Radio Autonomía con Bocafloja

26 de agosto 2012

Oscar Grant Plaza, Oakland, California

AUDIO de la Entrevista con Bocafloja

Radio Autonomía: Bueno, estamos acá en la ciudad de Oakland, California con Bocafloja, en Oscar Grant Plaza, donde hubo el campamento de Occupy Oakland el año pasado y un espacio bastante importante para las luchas de acá de Oakland. Vamos a hacer una pequeña entrevista sobe la cuestión de la educación en el hip-hop. Bueno, para empezar, nos puedes contar un poco de la historia del colectivo QuilomboArte, tal vez empezando con el nombre…

Bocafloja: Bueno, el colectivo QuilomboArte retoma el nombre de Quilombo como una forma de afirmar las cuestiones identitarias, especificamente las cuestiones raciales. El nombre de Quilombo viene de la época colonial y se remonta a esos espacios autónomos de esclavos e indios y negros que huían del regimen colonial para formar comunidades autónomas al margen de la colonia, desde donde podían incluso llegar a negociar con el propio sistema colonial. Entonces nosotros retomamos este nombre como una especie de metáfora de este proceso de lucha que nos influyó. Como colectivo llevamos publicamente al rededor de siete años, celebramos nuestro séptimo aniversario este 2012 y haciendo trabajo utilizando el rap como una herramienta de transformación, a través de la música.

RA: En el sitio web de QuilomboArte, http://www.emancipassion.com, hacen referencia al uso de herramientas no-ortodoxas de la educación. ¿Puedes explicar un poco qué significa esta idea?

BF: Basicamente estamos tratando de usar el rap y la poesía como una pedagogía contra-hegemónica. Estamos tratando de vincular con las comunidades marginales a través de elementos artísticos que son más relevantes para ellos. El rap es una experiencia y un lenguaje que en algunos casos pudiera ser más relevante, más cercano y más afable a los oídos, y a los ojos, y al entendimiento de muchos de los jóvenes que hablan este lenguaje de una forma más natural. Entonces utilizando estos elementos culturales y estas manifestaciones podemos romper las barreras jerárquicas que a veces existen en la transmisión del conocimiento. Entonces basicamente lo que intentamos es hacer un ejercicio de intercambio de cultura, en el cual no existan los formatos opresivos tradicionales que puede a veces reproducir la educación, donde hay alguien que dictamina cual es proceso y la información que se ha de recibir. Entonces tratamos de usar elementos culturales que no son hegemónicos—cultura que es más relevante para nuestra propia gente.

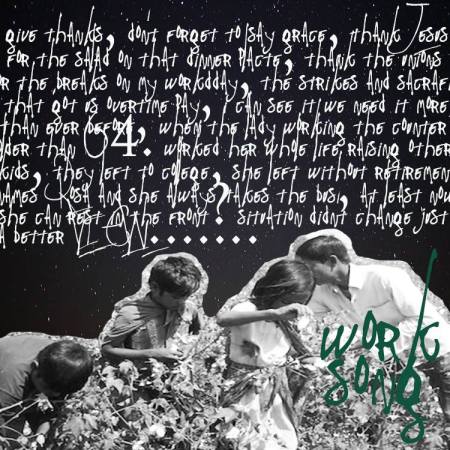

RA: Tu nuevo disco, Patologías del invisible incómodo, se describe como un album de concepto. ¿Puedes explicar un poco de la idea de este proyecto y qué significa que sea un “album de concepto”?

BF: La industria de la música hoy en día tiene un formato de producción que consiste basicamente en hacer “singles,” una colección de “singles.” Entonces estoy tratando con este album de trabajar enfocado en la idea de buscar un concepto donde cada una de las canciones tenga una conexión directa con la otra, que toda el album tenga una temática detrás. En el caso de este album, se habla sobre el cuerpo del oprimido como un vehículo de transgresión hacia los esquemas hegemónicos. Habla de la invisibilidad del hombre de color, transgrediendo estos espacios. Habla también de estas supuestas patologías o condiciones mentales que la colonización nos dejó como colonizados, y esta forma de relacionarnos con nuestro propio cuerpo, con la alimentación, con la sexualidad, con nuestra propia psicología. Eso es basicamente el tema del album.

RA: La semana pasada salió el tercer video del album, para la canción “Agonía” que trata la cuestión de la política de la comida, muy explicitamente. Nos pareció que el video tiene un objetivo pedagógico bastante fuerte, tanto en la letra pero también en el hecho de que el video está subtitulado en inglés y en español, para que un público hispanohablante o anglohablante pueda entender toda la letra. Nos puedes hablar un poco más de esta canción en particular, de la producción de este video y cómo esta canción sirve como un ejemplo de esta necesidad de crear más conciencia popular sobre un tema tan fuerte y tan urgente como es la comida.

BF: Como mencionas, es un tema urgente. Hay veces que hemos logrado naturalizar el alimento sin darnos cuenta que a través de la comida el proceso colonial y el sistema mercenario capitalista utiliza esta herramienta como una manera de exterminio de muchas de nuestras comunidades. Ejemplos hay muchos—comunidades y sociedades enteras están sufriendo de condiciones físicas super deplorables debido a este proceso de alimentación, que no solo tiene afectaciones psicológicas o físicas sino también económicas, sociales, culturales. Entonces yo tenía intención de hablar sobre esto de una manera en la que se pudiera exponer el tema en los dos idiomas considerando que no es un problema único de una comunidad en los EEUU, sino que es una cuestión que está pasando en cualquier parte del mundo y que era importante exponerlo y tratar de articularlo de esta manera. Es un tema muy relevante para mí, y creo que por eso fue la idea de hacer el video con los subtitulos.

RA: En otras canciones tuyas, en discos previos, aparece también este tema de la comida, ¿cómo llegó a tener un lugar tan importante para tí la comida en tu vida personal y política?

BF: Creo que aparece de la necesidad y la urgencia de ir un poco más profundo en el asunto de la comida, porque se divide basicamente en dos partes. Por un lado está tradicionalmente la posibilidad que tiene mucha gente de disasociar y decir “a mí no me importa, yo como lo que puedo, yo como lo que tenga capacidad de hacer o lo que me antoja”, sin darle mucha cabeza. Y por otro lado está la cuestión de las democracias liberales que promueven el consumo orgánico de ciertos productos, pero que responde a un sistema de privilegio, responde a un sistema que puede resultar parte de una elite, que puede ser una practica bastante excluyente, porque es un sistema de encarecimiento de los precios que hace completamente inaccesible el consumo de cierto tipo de comida a la gran mayoría de la población, que es la que en verdad está sufriendo de las condiciones de comer una comida de mala calidad. Entonces había que poner en evidencia e investigar más sobre estos dos lados. Sobre el por qué una persona no puede acceder a comida de mejor calidad por este sistema excluyente, y por qué esta persona tiene que tomar la decisión de comer basicamente lo que le llegue a la mano. Y como es que se puede hacer un cuestionamiento de estas comunidades más privilegiados que tienen la posibilidad de encarecer estos productos o que son cómplices de este encarecimiento y de esta industria. Entonces es una onda muy compleja y le intentamos ahí de alguna manera deconstruir en la canción “Agonía.”

RA: En todo tu trabajo se percibe una conciencia anti-colonial muy fuerte, con el tema de la emancipación apareciendo en todas partes. Creo que el rap sigue siendo un espacio muy dominado por hombres, el hip-hop dizque “conciente” es un espacio donde aparecen cada vez más mujeres, pero para mí es un problema que afecta todavía al hip-hop. Pensando en la conexión entre el hip-hop y la educación, y en el legado muy fuerte de feministas de color, feministas del “tercer mundo” en el desarrollo de la pedagogía radical, nos interesa saber un poco cómo ves el papel de una política anti-patriarcal dentro de tu trabajo, y dentro de estas iniciativas de crear un hip-hop más emancipatorio, un hip-hop más anti-sistémico, anti-estatal, anti-colonial, anti-capitalista…

BF: Creo que la responsabilidad que asumimos al intentar hacer una propuesta artística que rompa con todos estos sistemas de opresión y sistemas jerárquicos e históricos obviamente no puede dejar de lado la lucha anti-patriarcal. Nosotros mismos estamos tratando de emanciparnos de estos propios procesos internos y de aprender a reconocer nuestras propias contradicciones y de alguna manera caminar en esta dirección de liberarnos sobre esos asuntos. Creo que es fundamental… no sé si es un cuestión específica del hip-hop o si es cuestión del arte, que muchas de las comunidades oprimidas han manifestado, y las no-oprimidas. Es super fundamental hacer ese trabajo y de utilizar referentes que no solamente vengan de una sola linea de género. Creo que el hecho de participar y trabajar con más mujeres en los proyectos, de alguna manera le otorga otra posibilidad, otra cara, otro contexto al trabajo que hacemos. Yo siempre me he preocupado en este sentido. Creo que es importante no solo en terminos de la expresión artística trabajando con otras mujeres, sino también de los referentes intelectuales, y del trabajo y de la forma que nos relacionamos con otros proyectos. Es una de los conflictos más complejos a resolver porque todo el sistema cultural funciona de una manera muy determinada. Creo que el hip-hop es consecuencia de estos sistemas culturales que son excluyentes en la cuestión de género.

RA: ¿Qué es para tí una pedagogía radical? ¿Qué hace que una pedagogía rompa con los esquemas hegemónicos?

BF: Primero que nada, es una pedagogía que tiene como principio fundamental el hecho de empoderar a la persona que está aparentemente jugando el rol de escucha. Romper con la idea que hay una persona que transmite el conocimiento y hay otro que solamente lo recibe. Evidentemente el buscar referentes de información y autores y un sistema de cultura que sea benéfico y coherente con el capital y el sistema. O sea, no podemos seguir diciendo solamente que fomentar la lectura es un acto suficiente para poder seguir avanzando como pueblos o como individuos. No solamente se trata de leer, sino se trata de ver qué es lo que nuestra gente está leyendo. No se trata de revisar la historia, sino se trata de redefinir la historia. Entonces hablamos nosotros de este proceso de desaprendizaje, que estamos teniendo, no sé, llegamos a un punto en el que tenemos que de alguna manera resetearnos, empezar a borrar todo ese conocimiento que nos han impuesto para volver a aprender. Entonces, en ese sentido, la posibilidad de utilizar el arte con una plataforma pedagógica que se brinque todo ese proceso de años de información no-necesaria, errónea, manipulada, pues ya es un acto revolucionario por si mismo. Entonces es una cuestión fundamental para nosotros el poder encontrar estas nuevas maneras. Y otra cosa es que el rap nos otorga esta posibilidad de tener un impact directo con la gente, con cierto tipo de gente, con las comunidades que más nos interesan porque muchas veces de primera instancia es difícil hacer que la gente participe y esté interesada en una temática que para ellos puede parecer abstracta de primer impacto. Entonces a través del lenguaje del rap y un poco la experiencia de las comunidades y de la calle de alguna manera, podemos lograr captar su atención, y intercambiar a través de la utilización de un lenguaje más cercano.

RA: Bien! Pues estamos muy felices de tenerte acá en Oakland con nosotros. Muchísimas gracias!

Más información sobre Bocafloja y QuilomboArte, y links a videos, música y mucho más: www.emancipassion.c

Más información y los archivos de Radio Autonomía: radioautonomia.wordpress.com

——————————————————————-

[ENGLISH TRANSLATION]

Interview: Radio Autonomía with Bocafloja

August 26, 2012

Oscar Grant Plaza, Oakland, California

AUDIO of the Interview with Bocafloja

Radio Autonomía: So, we’re here in Oakland, California, in Oscar Grant Plaza, where Occupy Oakland set up its camp last year and which is an important space for struggles here in Oakland. We’re going to do short interview with Bocafloja on the theme of education in Hip-Hop. So to start off, can you give us a bit of the history of the collective QuilomboArte, maybe beginning with the name itself?

Bocafloja: Our collective QuilomboArte picks up the name Quilombo as a way to affirm issues of identity, specifically questions of race. The name Quilombo comes from the colonial era and refers to those autonomous spaces of slaves, indians and blacks who escaped the colonial regime to form autonomous communities on the margins of the colony, from there they were able to negotiate with the colonial system. So, we retake this name as a kind of metaphor for those struggles that have influenced us. As a collective, we’ve been working publicly for 7 years. This year we celebrated our seventh anniversary of working with rap as a transformative tool, through music.

RA: On QuilomboArte’s website (www.emancipassion.com), you refer to the use of non-orthodox educational tools. Can you explain a little bit about what this idea means?

BF: Basically, we try to use rap and poetry as a counter-hegemonic pedagogy. We’re trying to link up with marginal communities through artistic elements that are more relevant to them. Rap is an experience and a language that, in some cases, can be more relevant, closer, and more palatable to the ears, eyes, and the understanding of many young people who speak that language in a way that comes more naturally to them. So, using those cultural elements and examples we can break with the hierarchical barriers that sometimes exist in the communication of knowledge. Basically, what we try to do is an exercise in cultural exchange, without the traditional oppressive formats that education often reproduces, like when there is one person who judges what process and information others should receive. We try to use cultural elements that are not hegemonic—culture that is relevant for our people.

RA: Your new album, Patologías del invisible incómodo, is described as a concept album. Can you explain a bit about the idea behind this project and what it means to be a “concept album”?

BF: Today’s music industry has a format of production that basically consists in producing “singles”, or a collection of “singles.” With this album I’m trying the focus on a specific concept so that each song has a direct connection with the others, and the whole album has a theme behind it. In the case of this album, it speaks about the oppressed body as a vehicle of transgression against hegemonic structures. It speaks to the invisibility of the person of color, transgressing those spaces. It also speaks to these supposed pathologies or mental conditions that colonization has left us with as colonized people, and the way we relate to our own body, through food, sexuality, and our own psychology. That’s basically the theme of the album.

RA: Last week the third video for the album came out, for the song “Agonía”. It treats the question of food politics very explicitly. To us it seems that the video has an explicit pedagogical objective, as much in the lyrics as in the fact that the video is subtitled in English and Spanish so that Spanish speakers or English speakers can understand all the content. Can you tell us a bit more about this song in particular, about the production of the video and how this song serves as an example of the need to create more popular awareness about a theme as important and urgent as food?

BF: Like you mentioned, it’s an urgent topic. We’ve come to naturalize food without realizing the ways that the colonial process and the mercenary capitalist system use this tool as a form of extermination of many of our communities. There are lots of examples—communities and whole societies are suffering from seriously deplorable physical conditions because of this food system, which not only has physiological effects but also economic, social, and cultural effects. So, I had the intention of speaking about this issue in a way that it could be presented in two languages given that it’s not only a problem for communities in the United States but rather it’s something that’s happening all over the world, and it was important to address it and try to articulate it in those terms. It’s a really relevant issue for me, and I think that’s why the idea was to do the video with subtitles.

RA: In your other songs, on your previous albums, the issue of food also appears. How did the issue of food come to occupy such an important place for you in your personal and political life?

BF: I think it appears out of the necessity and urgency to go a little deeper into the issue of food because there are basically two parts. On one side, traditionally, there is the tendency that many people have to disassociate and say “I don’t really care, I eat what I can, I eat what I have the ability to make, or what sounds good to me”, without thinking much about it. And on the other side is the issue of liberal democracies that promote the consumption of organic products, which responds to a system of privilege, a system that can turn out to reproduce an elite, and that can turn into an exclusionary practice because it’s a system that raises the prices until it becomes impossible for the majority of people to access that food. And it’s those people who are suffering the condition of eating low quality food. So, that’s what I think should be made evident and investigated, these two sides. About why a person can’t get better quality food because of this exclusionary system, and why this person has to make the choice to eat basically whatever they can get. And, how can we make it possible to question those privileged communities who contribute to rising prices of these organic products or who are complicit with this industry. So, it’s a complex issue and it’s something that we’re trying to deconstruct in the track “Agonía”.

RA: In all of your work there is a clear anti-colonial consciousness, with the theme of emancipation appearing everywhere. I think we can say that rap continues to be a space dominated by men. In so-called “conscious” hip-hop there are more and more women appearing, but for me it’s a problem that still affects hip-hop. Thinking about the connection between hip-hop and education and the strong legacy of feminists of color, and third world feminisms in the development of radical pedagogy, we’re interested in hearing about how you see the role of anti-patriarchal politics in your work, and within these initiatives to create an emancipatory hip-hop, an anti-systemic, anti-state, anti-colonial, anti-capitalist hip-hop…

BF: I think that the responsibility that we assume when we attempt to develop an artistic proposal that breaks with all of those systems of oppression and hierarchical and historical structures can’t ignore the struggle against patriarchy. We ourselves are trying to emancipate ourselves from these internal processes and learning to recognize our own contradictions and somehow move towards liberating ourselves from these systems. I think it’s fundamental….I don’t know if it’s a question specific to hip-hop or if it is an issue that affects all art, and that many oppressed, and not oppressed, communities have faced. It’s really crucial that we do this work and use references that don’t only come from one particular gender identification. I think the participation and collaboration of more women in projects in some way offers another possibility, another face, another context to the work that we do. In this sense, it has always been a concern for me. I think that it’s important, not only in terms of artistic expression—working with women—, but also in terms of intellectual references, and in the work and the form that we relate to other projects. It is one of the most difficult conflicts to resolve because the whole cultural system functions in a really determinate way. I think that hip-hop is a consequence of those cultural systems that are exclusionary in terms of gender.

RA: What is radical pedagogy for you? What does a pedagogy that breaks with hegemonic structures do?

BF: Before anything, it has to be a pedagogy based on the principle of empowering the person who is the supposed listener or learner. It breaks with the idea that there is one person who transmits knowledge and there is another who only receives it. And clearly it’s about identifying information and references to authors and a cultural system that is benevolent and coherent with capital and the system. And we certainly cannot continue saying that simply promoting reading is enough to be able to continue advancing as communities or as individuals. It’s not just about reading, but about looking at what our people are reading. It’s not about revising history, it’s about redefining history. So, we talk about the process of unlearning…. We arrive at a point where we have to, in some way, reset ourselves, begin to erase all this knowledge imposed on us in order to start learning again. So, in this sense, the possibility of using art as a pedagogical platform jumping over this process of years of learning unnecessary, erroneous, manipulated information is already a revolutionary act in itself. So to be able to discover these new forms is fundamental for us. The other thing is that rap grants us the possibility to have a direct impact on people, on a certain type of person, and with the communities that interest us the most, because many times it’s difficult to get people to participate and be interested in an issue that for them seems abstract. So through the language of rap and the experience of these communities and the street, somehow we’re able to get their attention, and exchange ideas with them through the use of a language that is much more familiar.

RA: Great! We’re really happy to have you here in Oakland with us. Thanks so much!

For more information about Bocafloja and QuilomboArte and links to videos, music, and much more, go to www.emancipassion.com

For more information about Radio Autonomía and to check out our archives, go to: radioautonomia.wordpress.com