LA ENTREVISTA APARECE EN ESPAÑOL HASTA ABAJO DE ESTA PÁGINA

Interview with Cambio by Alita/Radio Autonomía

July 7, 2013

Oakland, California

This is an edited version of the interview. To listen to the full audio of the interview, click HERE.

Alita: We’re here with a friend of ours, Cambio, an MC from Watsonville. He’s gonna tell us about the work he’s been doing and specifically a new project that he’s just released. We met you through our good friend Bocafloja, who we know from DF and who we’ve interviewed here on Radio Autonomía before. But you’re actually from right here in California. Tell us a bit about where you’re from and how you got started making music?

Cambio: Thanks for having me. Originally, I’m from the Central Valley, from East Bakersfield. My family moved there a long time ago to work in agriculture, working the grapes… there’s a big history behind that area and I like to say that in East Bakersfield there’s not a lot for young people to do… like a lot of similar places. So I got involved in hip-hop music, and it made me feel good about myself. It started with my basketball experience. Like a lot of young people, playing basketball is how I met hip-hop and I fell in love with it and wanted to get involved with it. My older brother was rapping and I was following along but with my own little style. They were into bumping like NWA at the time, and I was bumping like Fresh Prince of Bel Air. You know, like a very different type of style, but the same type of hip-hop experience. And so that’s where I’m coming from—it’s the Central Valley, you know, there’s not a lot of things to do. I’d like to go back, and hopefully one day build collectives and do solid work over there.

A: You live in Watsonville now, right? And you have another important job, in addition to being a musician, that I think adds another dimension to your experience. Can you tell us about that and how it intersects with your music?

C: I’m a high school teacher now at a continuation high school called Renaissance High School. And I’ve been doing it for like seven years. I think that teaching and music is kind of the same thing. First I was a musician and rapper before I got into teaching. Teaching was kind of like what I got into by default. Like what can I do and travel at the same time? There’s other artists that I’ve spoken to like J-Live and others that are kinda doing something similar. It’s been a beautiful experience working with the young people in this type of atmosphere. I’m not gonna let the education system coopt rap music and water it down to further subjugate students or to facilitate their process of colonization… I’m gonna use it in a different way. So I never really wanted to become accepted too much by the school system in itself but I also want to use it as a vehicle to relate to young people and say, hey, this is a tool that we can use to relate to each other.

A: One of the things that’s really impressive about your work and the work of the folks you’re involved with in QuilomboArte is the fact that you are all independent artists. Can you tell us a bit about your experiences working with QuilomboArte and especially how it helps you move your work?

C: First, I met Bocafloja, because he was doing a show in San Jose and the promoter was playing my first album “The Bridge Called My Back.” And so he heard it and he reached out to me. He was one of the first “established” independent artists to reach out to me. I had reached out to a lot of people—this goes back to the independent hustle—I had reached out to many people in different areas, like “Hey, can we do a show together? Can we collaborate?” and no responses. And it took someone from 3000 miles away in Mexico City to reach out to this kid from the Central Valley/Watsonville area to be like “let’s collaborate, let’s go on tour… would you like to go on tour in Mexico?” And my response was, that’s a given, of course I would. So, being around him and his hustle, 100% independent, recording all his own stuff, having a little help with mixing and mastering, producing your own album, making it with quality and then giving it to the people by doing shows, doing interviews and that type of grind that he has, it’s rubbed off on me in a really beneficial way where recently we’re doing our own visuals. By default, not having the budget to necessarily pay like we were paying people to do, like $2000 to do a music video, now we’re gonna learn that hustle and we’re gonna do our own. So we’ve been producing our own visuals for the last year and a half. And being a part of the QuilomboArte collective, now I have an audience in Latin America that’s like crazy. It’s my number one audience. And it’s really ironic because you would think that it would be locally in this area, but it’s not… it’s far away.

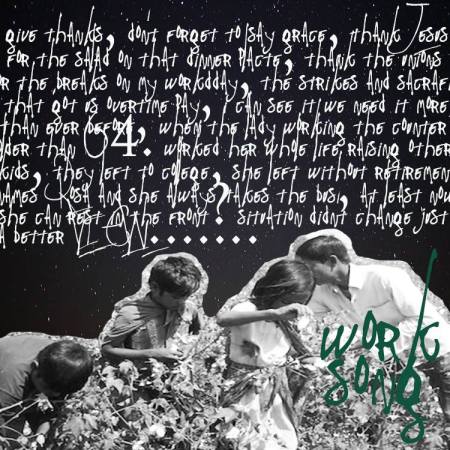

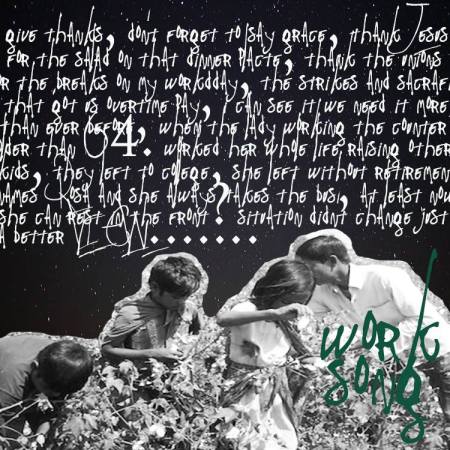

A: You know that this past week we saw a historic strike of BART workers in the area, shutting down public transit, and also on Monday the City of Oakland workers were on strike. And this brought up all kinds of interested discussions about labor and labor movements and organizing and the role of solidarity. As all this was happening, I was listening to your new record and I was really interested in the track “Work Song.” It reminded me a little bit of a song from one of your earlier albums “Fresh Kicks,” which has this narrative about the other side of work—the things and the people we don’t usually think about. I wanted to hear a bit about the experiences that influenced you as you wrote these rhymes.

C: I think most folks don’t know that one of my first jobs out of college was as a union organizer for Unite HERE in Baltimore, and my job was to organize undocumented hotel workers that were from Central America and didn’t speak English. And they were having issues with the African-American/Black workers at this spot, they were like beefing with each other, the workers were. And so that really informed a lot of the process in terms of the articulation and I kind of brought that back over here. I had ended the job, and I was like I’m gonna get into teaching. I was like, this union stuff is hard… shout out to anyone who does union organizing—it’s legit, hardcore work. So you’ll hear that in my music. My parents are workers, my father’s a worker, they work hardcore all the time. I remember since I was a young kid, my mom would say “Don’t cross a picket line.” Worker solidarity, we’re the workers. Where do we live? We live in the hood. We work here. We do everything for everybody. So the song “Work Song” starts with “Give thanks don’t forget to say grace, thank Jesús for the salad on that dinner plate” with Jesús not being god, but being the homie from down the block, picking our salad. And another verse talking about my pops: “I got a stubborn old man, three heart attacks can’t get him to relax, surprise surprise he’s working in the back…” So I always try to stand in solidarity first and foremost with workers’ movements.

A: A theme that comes up in a different one of your songs, “Jumping Fences,” which we heard you perform spoken word style at the Holdout here in Oakland a while back, is the fact that you’re a US-based Chicano artist who raps in English and tours in Latin America. I was really kind of surprised when I looked at the Bandcamp site of your new record and saw that you have Spanish translations of your lyrics on the website. I’d love to hear a bit about how language works for you, why you translate your lyrics, and the kinds of challenges you’ve faced as a Chicano in the Latin American hip-hop scene.

C: First of all, Bocafloja is always on me about the lyrics, telling me “Translate the lyrics! Put it on YouTube!” The audience that I have is in Latin America. But I’m horrible at rapping in Spanish, so I don’t even try. So I try to put translations up so people can understand what I’m saying. That’s helped grow my audience, and I’m not trying to leave or be specific to a US audience. You know, if I could put it in 8 languages, I really would try to put it in as many languages as possible. So “Jumping Fences” is a song that I write dealing with borderlands again, is more about me and my issues within the Chicano community in California and some of the critiques that I may have, or about not feeling validation from certain communities as a legit Chicano-indigenous type of rapper that’s stereotypical within the California context. So that’s the type of issues I’m talking about on the song, but I’m giving you a history in the song, I’m saying: Listen. My father watched the Lakers, basketball, R&B music, Luther Vandross. It wasn’t like a stereotypical Latino type of thing, with like banda music playing. That’s dope, but it just wasn’t in our house. So it was different, and I’m gonna rap about different things and the style’s gonna be different. And what informed me as a Chicano is different, it’s gonna be different. So I have these critiques—no, I didn’t pop out of a Edward James Olmos movie. I didn’t come out of that. I’m from hardcore gang areas, but it doesn’t mean I have to replicate that. And that’s okay. It took an artist from another place to say: “It’s okay, just be yourself. It’s valid. Your experience is valid… So continue to say and do what you wanna say and do.” I was getting critiques from certain audiences in different areas in California, being like “You’re not this enough… You don’t really fit in. You’re not really an indigenous rapper” with like the certain manifestation of what they feel that is. And “You’re not really like gangster Chicano rap” at the same time, which is usually coming out of Central Valley or certain areas. And “You’re a Latino rapper but you’re not from ‘Latin America,’ you’re not from Mexico City.” You can’t really exoticize me too much. It’s just not that “hip” to a lot of audiences. Whereas if it was like a big exotic zoo and everyone’s looking at these Latino artists that play the drums and nice guitars and stuff. I don’t really have any of that. So the song is definitely poking at those ideas. It’s one of my favorite songs.

A: Your music comes from the experiences that you’ve lived but also clearly from things you’ve read and movements you’ve been plugged in with. Can you give us a sense of some of the most influential thinkers or political movements that are with you as you write your music?

C: I think the number one, one of the main influences is Muhammad Ali. His connection to everyday working folks during the time period is very important. He was at the height of his career, he chose particularly to take a certain stand which I feel like no athletes or people in that position do today. And what he stood for was very important, and I think that everyday people related to him. Which brings me to the next group, the Black Panther Party has huge influence as far as politics, style, the way they related to everyday common folks is definitely what I try to do in the music, before anything else. Relate to everyday people. That’s my inspiration. In the first track of this album I’m very particular of who my inspiration is: “For the places unfinished at our creation, we learning from early ages engaging imagination, and everyday common hustle the canvas to my design.” Everyday common people, and that’s gonna continue to be my inspiration. And when we travel meeting people, like yourself, or coming across beautiful people like when we were in Germany and met different people that extended their hand out to us having conversation and connecting. And they plug us in to their movements and what they’re doing, and that type of love is what I’ll write about for days.

A: If folks want to check out the new album and learn more about your work, where can they find it?

C: You can find it on Bandcamp: cambio.bandcamp.com or if you Google “Cambio QuilomboArte” you’ll find all the work on YouTube or wherever. I also have physical CDs for sale at upcoming shows.

A: Thanks so much. We’re gonna go out here with a track from the new album called “Work Song.”

———

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Radio Autonomía

Entrevista a Cambio (por Alita/Radio Autonomía)

7 de julio 2013

Oakland, California

Este texto es una traducción de una versión editada de la entrevista original. Para escuchar el audio completo en inglés haz click AQUÍ.

Alita: Estamos aquí con nuestro amigo, Cambio, un MC de Watsonville. Nos va a hablar del trabajo que ha estado haciendo y de su nuevo proyecto. Te conocimos hace muchos años en Chiapas a través de nuestro amigo Bocafloja, quien conocemos del DF y hemos entrevistado también en Radio Autonomía. Pero tú eres de aquí de California. Cuéntanos de dónde eres, y cómo es que empezaste a hacer música.

Cambio: Gracias! Yo soy del Valle Central de California, de East Bakersfield. Mi familia llegó a la zona hace muchos años para trabajar en la agricultura, en la cosecha de uvas… Hay una larga historia en esa zona, y yo siempre digo que en East Bakersfield no hay mucho que hacer para los jóvenes.. como en muchos lugares parecidos. Entonces yo me involucré en el mundo del hip-hop, y empecé a sentirme bien de mi mismo. Empezó con mi experiencia jugando basquetbol… Como muchos jóvenes, fue a través del basquetbol que me hallé con el hip-hop y me enamoré y quería meterme en ese mundo. Mi hermano mayor ya estaba rapeando y yo lo seguía pero con mi propio estilo. Ellos escuchaban NWA mientras que a mí me gustaba Fresh Prince of Bel Air. Un estilo muy distinto pero la misma experiencia del hip-hop. Entonces de ahí vengo—es el Valle Central, no hay mucho que hacer. Me gustaría regresar, para un día tal vez organizar un colectivo y hacer buen trabajo allá.

A: Ahora vives en Watsonville, verdad? Y, además de ser músico, tienes otro trabajo muy importante que creo que le da otra dimensión a tu experiencia. Nos puedes contar de tu trabajo y como se cruza con tu música?

C: Soy maestro en una preparatoria de continuación que se llama Renaissance High School. Hace siete años que enseño. Y yo creo que la enseñanza y la música son cosas muy parecidas. Empecé como músico y rapero antes de empezar a enseñar. Tomé la decisión de ser maestro porque estaba buscando una profesión que me permitiera viajar también. Hay otros artistas con quienes he hablando que están haciendo algo parecido, como J-Live por ejemplo. Trabajar con jóvenes en este tipo de ambiente ha sido una experiencia lindísima. Pero no voy a permitir que el sistema educativo coopte el rap o lo diluya para avanzar la subyugación de los estudiantes o facilitar su proceso de colonización. Lo quiero usar de otra forma. Nunca me interesó ser aceptado por el sistema escolar, pero lo quise usar como un vehículo para conectar con los jóvenes y decirles que está chido—que podemos usar la escuela como un medio para encontrarnos.

A: Un aspecto interesante de tu trabajo y el trabajo de tus compas del colectivo QuilomboArte es el hecho de que todxs son artistas independientes. Nos puedes contar un poco de tus experiencias como parte de QuilomboArte y especialmente como te ha ayudado a mover tu trabajo?

C: Bueno, conocí a Bocafloja porque él estaba haciendo una tocata en San José (California) y antes de su set el organizador estaba tocando mi primer disco “The Bridge Called My Back” (El puente llamado mi espalda). Entonces ahí Bocafloja escuchó mi disco y me contactó. Fue uno de los primeros artistas “establecidos” que me buscó. Yo había tratado de contactar a muchos artistas—es parte de la movida independiente—preguntándoles “Oye, no quieren hacer una tocata juntos? Podemos colaborar?” y nada. Fue alguien de más de 4000 km al sur en la Ciudad de México que me buscó y me dijo “colaboremos, hagamos una gira juntos… quieres hacer una gira en México?” Y yo le contesté, claro, obvio, como no!? Entonces, la experiencia de estar con él y su movida 100% independiente, grabando toda su propia música, con un poco de ayuda con el mastering y las mezclas, produciendo sus propios discos, haciendo todo con calidad, y compartiendo lo que hace con la gente a través de sus conciertos, de entrevistas y todo lo demás, eso me ha afectado mucho de una forma muy positiva… recientemente hemos empezado ha hacer nuestra propia producción visual. Por necesidad, como no tenemos lana para pagarle a otra gente, por ejemplo, $2000 dólares para hacer un videoclip, ahora decidimos aprender a hacerlo nosotros mismos. Y ahora como parte del colectivo QuilomboArte tengo un público en América Latina—es bien loco, es mi público principal. Es un poco irónico porque uno pensaría que mi público principal estaría aquí en Califas, pero no… está bien lejos.

A: Como sabes, aquí en la Bahía vimos una huelga histórica de trabajadores del metro (BART), además de una huelga el lunes de los trabajadores municipales de la ciudad de Oakland. Éstas huelgas abrieron discusiones interesantes sobre el trabajo, los movimientos de trabajadores, y el papel de la solidaridad en estos procesos. Mientras que todo esto estaba sucediendo, empecé a escuchar otra vez tu nuevo disco, y me quedé pensando en la canción “Work Song.” Me recordó un poco de una canción que aparece en uno de tus primeros discos “Fresh Kicks,” que cuenta una historia desde una perspectiva laboral que generalmente se oculta. Nos puedes contar un poco de las experiencias que te influyeron cuando estabas escribieron estas canciones?

C: Creo que mucha gente no sabe que mi primer trabajo cuando terminé mis estudios universitarios fue como organizador sindical con Unite HERE en Baltimore. Mi trabajo fue de organizar los trabajadores indocumentados de Centroamérica que trabajaban en los hoteles y que no hablaban inglés… y llevé esa experiencia de vuelta a California cuando terminé ese trabajo. Tomé la decisión de ser maestro, porque para mi el trabajo con el sindicato fue muy difícil… quiero reconocer a toda la gente que se dedica a eso porque es trabajo importante y pesado. Entonces eso se percibe en mi música. Mis papás son trabajadores, mi jefe trabaja, trabajan duro todo el tiempo. Y me recuerdo desde chiquito mi mamá me decía “Nunca cruces un piquete.” Solidaridad con los trabajadores, somos los trabajadores. Dónde vivimos? Vivimos en el barrio. Aquí trabajamos. Hacemos todo para todo el mundo. Entonces la canción “Work Song” empieza así: “dar gracias, no te olvides de dar las gracias, gracias a Jesús por esta ensalada en este plato..” y aquí Jesús no es dios, es el cuate del barrio, que cosecha nuestra lechuga. En otro verso habló de mi papá: “tengo un viejo terco, ni ataques al corazón hacen que se relaje, que sorpresa—él está trabajando atrás…” Entonces antes que nada siempre intento solidarizarme con los movimientos de los trabajadores.

A: Un tema que surge en otra canción “Jumping Fences,” que presentaste estilo spoken-word aquí en Oakland hace unos meses, es el hecho que eres un artista chicano de los EEUU que rapea en inglés y hace giras en América Latina. Cuando entré a tu página de Bandcamp me quedé sorprendida cuando vi traducciones al español de la letra de tus canciones. Nos puedes platicar un poco de como manejas el tema del idioma, por qué traduces tus letras, y qué tipo de desafíos has enfrentado siendo un chicano en el mundo del hip-hop latinoamericano?

C: Bueno, Bocafloja siempre me joda por el tema de la letra de mis canciones—me dice “tienes que traducir todo! Ponlo en YouTube!” Mi público principal está en América Latina. Pero no puedo rapear bien en español, así que ni lo intento. Entonces intento publicar traducciones para que la gente pueda entender lo que digo. Eso me ha ayudado mucho a conectarme con más gente—no es que quiero irme de aquí ni dirigirme exclusivamente a un público gringo. Si pudiera, tendría traducciones a 8 idiomas! De veras, me gustaría traducir mi letra a todos los idiomas posibles. Entonces “Jumping Fences” es una canción que escribo regresando al tema de la frontera, y se trata más de los pedos que tengo con la comunidad Chicana en California y críticas que tengo, o de como me siento deslegitimado por algunas comunidades por no parecer el típico rapero chicano-indígena que es un estereotipo dentro del contexto californiano. Son algunos de los temas que trato en la canción, pero también te cuento mi historia. Digo: Mi papá veía a los LA Lakers—basquetbol; música R&B—Luther Vandross. Mi vida no fue la típica onda latina, con banda tocando en mi casa. Eso está chido, pero no fue mi experiencia. Fue diferente, entonces voy a rapear de cosas distintas y el estilo también va a ser distinto. Lo que informó mi experiencia como chicano fue diferente… Entonces tengo algunas críticas—no salí de una película de Edward James Olmos. No salí de eso. Soy de una zona muy intensa por la presencia de las pandillas, pero es no implica que lo tengo que replicar… y eso está bien. Tuve que conocer a un artista de otro lugar para sentir que está bien que sea quien soy, que es válida mi experiencia, y que debería de seguir diciendo y haciendo lo que quiera. En diferentes partes de California he recibido crítica por gente que me dice “No eres así… o no eres como nosotros…o no eres un rapero indígena…” O también “no eres un rapero chicano gangsta,” eso generalmente desde el Valle Central. O “eres un rapero latino pero no eres de América Latina, no eres del DF.” Lo que pasa es que realmente no me puedes exotificar. Pero lo que soy no es tan “cool” para muchos públicos. Mientras que muchas ven los artistas latinos que tocan los tambores o la guitarra y todo eso… Pero yo no tengo nada de eso. Entonces la canción juega con esas ideas. Es una de mis canciones favoritas.

A: Tu música nace de tus experiencias pero también claramente de cosas que lees o movimientos y espacios que has conocido. Nos puedes dar una idea de algunos de los pensadores o movimientos políticos que te acompañan cuando escribes tu letra?

C: Primero, una de mis influencia centrales es Muhammad Ali. Su conexión a la gente trabajadora corriente de su época fue muy importante. Él estaba a la cumbre de su carrera y decidió de tomar una cierta posición que ningún otro atleta ni persona famosa se atrevía a tomar. Y su posición política fue muy importante, y creo que la gente común y corriente se podía identificar con él. Y eso me lleva a la segunda influencia: las Panteras Negras. Ese grupo me influyó desde la política, el estilo, y también su relación a la gente común, porque eso es lo que busco hacer en mi música, antes que nada. Relacionarme con gente común. Esa es mi inspiración. En la primera canción del disco digo muy directamente quién es que me influye: “Para los lugares dejados abandonados al momento de nuestra creación, hemos aprendido desde niños encender la imaginación, el hustle diario es el lienzo para mi diseño.” La gente común y corriente seguirá siendo mi inspiración. Por ejemplo cuando viajamos, y conocemos a gente, como tú o la hermosa gente que conocimos en Alemania.. gente que nos invita a platicar y conocer sus mundos. Y nos conectan a sus movimientos y lo que están haciendo… es el amor del cual puedo pasar días enteros escribiendo.

A: Si alguien quiere escuchar tu nuevo disco y conocer más de tu trabajo, dónde lo pueden encontrar?

C: Todo se encuentra en mi página en Bandcamp: cambio.bandcamp.com o si buscas en Google “Cambio QuilomboArte” encontrarás todo en YouTube. También tengo discos en venta en los próximos eventos.

A: Muchísimas gracias! Vamos a salir con una canción del nuevo disco, “Work Song.”